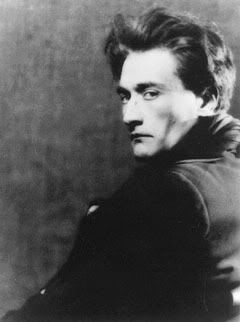

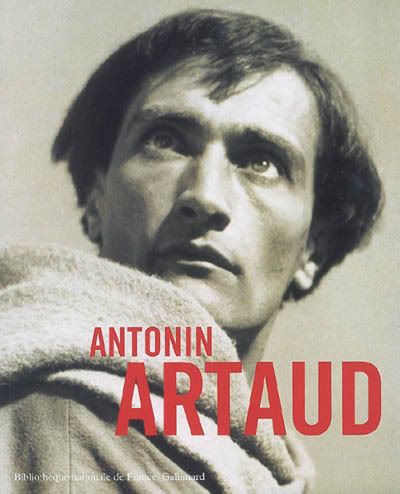

Genius or Madman: ANTONIN ARTAUD

ANTONIN Artaud's name is associated with a fundamental revolt against insincerity, and especially against insincerity in literature, where the written word corresponds to an attitude or a prejudice. His most cherished dream was to found a new kind of theatre in French which would be, not an artistic spectacle, but a communion between spectators and actors. As in primitive societies it would be a theatre of magic, a mass participation in which the entire culture would find its vitality and its truest expression. In January 1947, a year before his death, Artaud gave a lecture in Paris, in Copeau's old theater, the Vieux-Colombier. Among those present, and mingled with a youthful, fervent audience, were such writers as Gide, Breton, Michaux, and Camus. Artaud symbolized for all the generations in his audience an exceptional fidelity to a very great belief, a life devoted to a cause and an unflinching persistence in extolling the cause.

He was born in Marseille and spent his childhood in Provence and Smyrna. He studied in Marseille. At the age of eighteen, he was briefly cared for in a sanitorium for mental disorder. There were other attacks in 1916. In 1918 he went to a clinic for two years. In 1921 he acted for Lugné-Poë at the Théâtre de l'Oeuvre and for Dullin at the Atelier. He was engaged by Pitoëff in 1923. At this time some of his poems were published in literary magazines. He was one of the early followers of surrealism. In Paris he lived with his mother between 1924 and 1937. He was strongly attracted to the movies and played the role of the monk Massin in Carl Dreyer's Passion de Jeanne d'Arc of 1922. In 1927, for approximately one year he severed all connections with surrealism, and founded the Théâtre Alfred Jarry, which lasted for two seasons.

Of major importance in the evolution of Artaud's thought was the Colonial Exposition of 1931, where he was able to observe performances of the Balinese theater. These were the immediate origins of his conception of the Theater of Cruelty for which he wrote the First Manifesto in 1932 and the Second Manifesto in 1933. In May 1935, Artaud produced his play, Les Cenci, based upon a play of Shelley and a short story of Stendhal. Performances ran only two weeks. He spent part of 1936 in Mexico. Between 1939 and 1943 he was in a sanitarium. The year after his release, in 1944, his most important writing on the theater, Le Théâtre et son double (The Theatre and Its Double), was republished. Artaud died in 1948.

From this brief biographical sketch, it is obvious that Artaud's greatest activity in the theater fell approximately between the years 1930 and 1935. They were productive years for the Paris theaters in general. Jouvet produced three new plays of Giraudoux: Electra, La Guerre de Troie n'aura pas lieu, and Ondine. Dullin was responsible for a fine production of Richard III. Pitoëff put on three plays of Chekhov: The Sea Gull, Three Sisters and Uncle Vanya. But even such repertories as these were unsatisfactory for Artaud. He wanted to go much further in dramatic experimentation, desiring for the theater the same kind of frenzy and moving violence that he found in the paintings of Van Gogh. He claimed that a new kind of civilization was needed, one that would consummate a break with the sensitivity and the logival mentality of the nineteenth century. Thunderingly he denounced his age for having failed to understand the principal message of Arthur Rimbaud.

Artaud summarized the classical tradition of the French theater, which he found still dominant, as that art which states a problem at the beginning of a play, and solves it by the end. It is an art form, he says, that presents a character at the beginning and then proceeds to analyze the character during the remainder of the play. Artaud questions the authority of this procedure. "Who says that the theater was created to elucidate a character and to solve a conflict?" He claims that already in France there have been signs of a new kind of theater, one that is characterized by freedom, by the surreal, and by mystery. He sees the beginnings of this theater in Mallarmé, in Maeterlinck, and in Alfred Jarry. He finds an instance of it in Apollinaire's Les Mamelles de Tirésias, which he opposes to the then popular plays of Bernstein and François de Curel. The most successful plays of playwrights such as Sartre and Anouilh are closer to the traditional form of the French play, even to the form of a Bernstein, than to the experimentalism of an Apollinaire or a Jarry. As yet, the theories of Artaud have rarely been put into practice.

In analyzing his particular mission in the theater, Artaud divides humanity into two groups: the primitive or pre-logical group and the civilized or logical group. The roots of the real theater are to be found in the first group. At the Colonial Exposition of 1931, where he saw the Balinese theater, he was struck by the tremendous difference between those plays and our traditional Western play. He felt that the Balinese dramatic art must be comparable to the orphic mysteries that interested Mallarmé. A dramatic presentation should be an act of initiation during which the spectator will be awed and even terrified--and to such a degree that he will lose control of his reason. During that experience of terror or frenzy, instigated by the dramatic action, the spectator will be in a position to understand a new set of truths, superhuman in quality.

Although Artaud was usually condemnatory of Christianity, he defined the goal of the theater in spiritual terms. Its "sacred" goal, he claimed, is to communicate delirium whereby the spectators will experience trances and inspiration. Dramatic art induces as strong a delirium as a plague does. A true play, according to Artaud's concept, will disturb in the spectator his tranquillity of mind and his senses, and it will liberate his subconscious. Aristotle had emphasized especially the ethical power of the theater. Artaud intends to release its mediumistic force. If the theater is able to exalt man, it will drive him back to the mysterious primitive forces of his being.

The method Artaud proposes by which this will be brought about is to associate the theater with danger and cruelty. "This will bring the demons to the surface," he says. Words spoken on the stage will then have the power they possess in dreams. Language will become an incantation. Here again Artaud draws upon the poetic theory of Mallarmé and Rimbaud. Action will remain the center of the play, but its purpose is to reveal the presence of extraordinary forces in man. The metteur-en-scène becomes a kind of magician, a holy man, in a sense, because he calls to life themes that are not purely human. To illustrate this kind of spectacle Artaud equates it with certain paintings of Grünewald and Hieronymus Bosch.

The one experiment in Artaud's theater of cruelty was Les Cenci, his adaptation of the texts by Shelley and Stendhal. It initiated the fundamental notion of a "theater in the round," which has been especially developed in America, and which was destined by Artaud to establish a closer contact between actors and spectators than the normal theater could ever realize. In this production mechanical devices were used to create a visible and audible frenzy: strident and dissonant sound effects, whirling stage sets, the effects of storms by means of light, unusual speech effects. It was often difficult to distinguish between tragedy and the Grand Guignol.

Certain mass movements used by Jean-Louis Barrault in some of his productions are reminiscent of Artaud's Cenci. This production of 1935 marked a return in the French theater to a complicated stage production, which has been developed especially by Barrault (who had a part in the original performances of Artaud's play). The production was a failure, although some of the discerning critics, such as Jouve in the Nouvelle Revue Français, praised the stage set of Balthus and the direction of Artaud.

Out of the financial failure of Les Cenci, Artaud emerged as a prophet of the theater. His madness, accepted by some as a real sickness, has been interpreted by others as a sign of his revolt. He became a martyr of illogicality by protesting against morality and rationality. To be an actor for Artaud is equivalent to suppressing in oneself traits that make one distinct from other men. It is therefore equivalent to a kind of suicide. The last long internment of Artaud was interpreted by the surrealists as purely arbitrary, as a sign of the persecution that society is constantly imposing on revolutionaries and dissidents. However one interprets the terrifying obsessions of Artaud, they allowed him to see into unusual depths of the human mind, where he claimed the eternal questions on life and death are clearly visible.

The principal tenet of The Theater and Its Double states that reform in the modern theater must begin with the production itself, with the mise-en-scène. Artaud looks upon it as something far more than a mere spectacle: it is a power able to move the spectator closer to the absolute. The Oriental theater, which Artaud saw as a compact agglomeration of gestures, signs, postures, and sounds, constituted for him the language of production and staging. (Le langage de la réalisation et de la scène. . . .) The result of this kind of réalisation (which seems to be the more effective French word for our term "production") is the awakening of the spectator's thought, which will take attitudes that are "metaphysical in action." (La métaphysique en activité. . . .)

The real objective of the theater for Artaud is the translation of life into its universal immense form, the form that will extract from life images in which we would have pleasure in being. This is what he means by the word "double" (Le Théâtre et son double). The theater is not a direct copy of reality; it is of another kind of dangerous reality where the principles of life are always just disappearing from beyond our vision. He compares these principles to dolphins, who as soon as they show their heads above the surface plunge down into the depths. This reality is beyond man, with his habits and character. It is inhuman. If the theater is able to lead the spectator back into his world of dreams and primitive instincts, he will find himself "in a world that is bloodthirsty and inhuman" (sanguinaire et inhumain). Artaud has acknowledged that in this conception of the theater, he is calling upon an elementary magical idea used by modern psychoanalysis wherein the patient is cured by making him take an exterior attitude of the very state that he should recover or discover. A play that contains the repressed forces of man will liberate him from them. By plastic graphic means, the stage production will appeal to the spectators, and will even bewitch them and induce them into a kind of trance.

The Western theater has always been too dependent on a text. The Eastern theater is able to furnish a physical and not a verbal idea of theater. Theater in the West is associated with literature, whereas the Balinese productions that Artaud had seen were addressed to the entire being of the spectator and the words used in them were incantatory. Artaud wanted to see stage gesticulations elevated to the rank of exorcisms. In keeping with the principal tenets of surrealism, Artaud would claim that art is a real experience that goes far beyond human understanding and attempts to reach a metaphysical truth. The artist is always a man inspired who reveals a new aspect of the world.

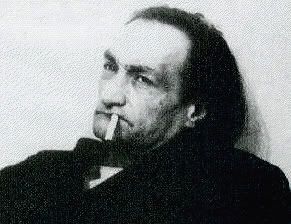

Shortly before Artaud died.

MANIFESTO IN A CLEAR LANGUAGE

by Antonin Artaud

If I believe neither in Evil nor in Good, if I feel such a strong inclination to destroy, if there is nothing in the order of principles to which I can reasonably accede, the underlying reason is in my flesh.

I destroy because for me everything that proceeds from reason is untrustworthy.I believe only in the evidence of what stirs my marrow, not in the evidence of what addresses itself to my reason. I have found levels in the realm of the nerve.

I now feel capable of evaluating the evidence. There is for me an evidence in the realm of pure flesh which has nothing to do with the evidence of reason. The eternal conflict between reason and the heart is decided in my very flesh, but in my flesh irrigated by nerves. In the realm of the affective imponderable, the image provided by my nerves takes the form of the highest intellectuality, which I refuse to strip of its quality of intellectuality. And so it is that I watch the formation of a concept which carries within it the actual fulguration of things, a concept which arrives upon me with a sound of creation. No image satisfies me unless it is at the same time Knowledge, unless it carries with it its substance as well as its lucidity. My mind, exausted by discursive reason, wants to be caught up in the wheels of a new, an absolute gravitation. For me it is like a supreme reorganization in which only the laws of illogic participate, and in which there triumphs the discovery of a new Meaning. This Meaning which has been lost in the disorder of drugs and which presents the appearance of a profound intelligence to the contradictory phantasms of the sleep. This Meaning is a victory of the mind over itself, and although it is irreducible by reason, it exists, but only inside the mind. It is order, it is intelligence, it is the signification of chaos. But it does not accept this chaos as such, it interprets it, and because it interprets it, it loses it. It is the logic of illogic. And this is all one can say. My lucid unreason is not afraid of chaos.

I renounce nothing of that which is the Mind. I want only to transport my mind elsewhere with its laws and organs. I do not surrender myself to the sexual mechanism of the mind, but on the contrary within this mechanism I seek to isolate those discoveries which lucid reason does not provide. I surrender to the fever of dreams, but only in order to derive from them new laws. I seek multiplication, subtlety, the intellectual eye in delirium, not rash vaticination. There is a knife which I do not forget.

But it is a knife which is halfway into dreams, which I keep inside myself, which I do not allow to come to the frontier of the lucid senses.

That which belongs to the realm of the image is irreducible by reason and must remain within the image or be annihilated.

Nevertheless, there is a reason in images, there are images which are clearer in the world of image-filled vitality.

There is in the immediate teeming of the mind a multiform and dazzling insinuation of animals. This insensible and thinking dust is organized according to laws which it derives from within itself, outside the domain of clear reason or of thwarted consciousness or reason.

In the exalted realm of images, illusion properly speaking, or material error, does not exist, much less the illusion of knowledge: but this is all the more reason why the meaning of a new knowledge can and must descend into the reality of life.

The truth of life lies in the impulsiveness of matter. The mind of man has been poisoned by concepts. Do not ask him to be content, ask him only to be calm, to believe that he has found his place. But only the madman is really calm.

this blog is dedicated to showcasing obscure rare and transgressive film video literature art and people including interviews reviews observations and anything else that I consider noteworthy and/or unconstitutional and deemed sinful or immoral by any religious right. I welcome you to send me queries comments or criticisms. -A.S.

this blog is dedicated to showcasing obscure rare and transgressive film video literature art and people including interviews reviews observations and anything else that I consider noteworthy and/or unconstitutional and deemed sinful or immoral by any religious right. I welcome you to send me queries comments or criticisms. -A.S.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home